Topics

Importance and Benefits of Async-IO Programming

Evidence for the importance of Asyncio in the modern tech market

Javascript VS Python

Multithreading Approach

Cloud-fit project Comments

part I

asyncio is great, and has evolved, but is still confusing and not sometimes mis-understood, misused

Python Docs are good but not great.

Not many useful tutorials, mostly basic and primitive concepts with not useful recipes

It’s not about using multiple cores, it’s about using a single core more efficiently. Multiple loops can run on multiple processes for further scaling

This scales very well with improved CPU core speeds

Coroutines are different from subroutines in that the can yield control back to the caller when it is known upfront that they are getting to a blocking point in the program

An Event loop runs on one thread

The event loop contains a list of objects called Tasks. Each Task maintains a single stack, and its own execution pointer

At any one time the event loop can only have one Task actually executing, while any other tasks in the loop remain paused

A running task will remain running on its event loop thread until it runs into an await statement or finishes all statements - it has to explicitly yield control. that’s why CPU intensive tasks are not recommended on event loops

part II

async def,async withandasync forare keywords to define an asyncio context where await can be usedtype hints is a good point, how do we deal with that

distinction between coroutine functions, objects and types

Python Async-IO - Part I: A Fresh look

Asynchronous programming at a high level

Non-blocking, Asynchronous, Event-driven programming is an important aspect of modern, high performance web applications that aim to be efficient and scalable in serving a large number of clients, and, to a great degree, capable of optimally utilizing the underlying system resources in production.

The creators of Javascript and its runtime engines have certainly figured that out a long time ago, making the non-blocking style as the default way of thinking and programming in JS - it is practically impossible to write blocking IO Code in JS! Making it one of the more advanced programming languages - in my opinion - when comes to building non-trivial applications.

Asynchronous programming is commonly regarded as the more difficult way. I generally disagree - I think it is essentially a different style and thought process, and a different set of idioms that need to be deliberately studied and internalized, which comes naturally to JavaScript professionals whose default has always been the asynchronous approach.

For instance, here’s one common way to fetch an HTTP resource (cryptocurrency prices in this case) and write it to a local file using Javascript running on Node.js, entirely in a non-blocking programming style:

const https = require('https')

const fs = require('fs')

https.get("https://api.coinlore.net/api/tickers/", (res => {

let http_data = ''

res.on('error', err => {

console.log(err)

})

if (res.statusCode === 200) {

res.on('data', (chunk => {

http_data += chunk

}))

res.on('end', (ev) => {

fs.writeFile('./coins.json', http_data, err => {

console.log(err)

})

})

}else {

console.log(`HTTP Request Unsuccessful: status code ${res.statusCode}`)

}

}))

If you are not used to reading JS code, this might look strangely out-of-order and unintuitive at first, or even ugly and scary to some people.

If that is you, relax, this article is about Python and not JavaScript. However, as a side note, if you are a serious current or a future software developer, keep in mind that JS is the language of the web, it runs on every browser on every PC and smartphone, and is slowly becoming one the most popular server-side languages running on Node.js, which is an excellent engine, and by the way, is traditionally much, much faster than Python. Therefore, becoming comfortable, or at least familiar with JavaScript and how it works is an increasingly essential skill these days.

Here’s what the program above does:

after importing the necessary modules, provide a URL for the resource, and start an HTTP request Asynchronously

During establishing a TCP connection, if an error occurs, print it to the console and exit

Otherwise, if TCP connection is successful, read HTTP status code from the response header and see if it is HTTP status 200

process every data chunk of data as it arrives in an IP packet received from the resource server

When the entire HTTP response has been received, open a file, ask the OS to make its own copy of the variable in RAM, and write it to disk asynchronously

Problems with blocking programs

Too convoluted? Sure, in comparison with a traditional Python implementation:

import requests

with open('./coins.json', 'w') as f:

f.write(requests.get("https://api.coinlore.net/api/tickers/").text)

Which is much more readable and more intuitive, even if we include some basic error handling code:

import requests

try:

with open('./coins.json', 'w') as f:

f.write(requests.get("https://api.coinlore.net/api/tickers/").text)

except Exception as ex:

print(ex)

Still looking nice and clean. The main issue with Python’s synchronous implementation is that it blocks the Python OS process a few times during HTTP connection and data retrieval, and at least twice during the opening and writing to the file on disk.

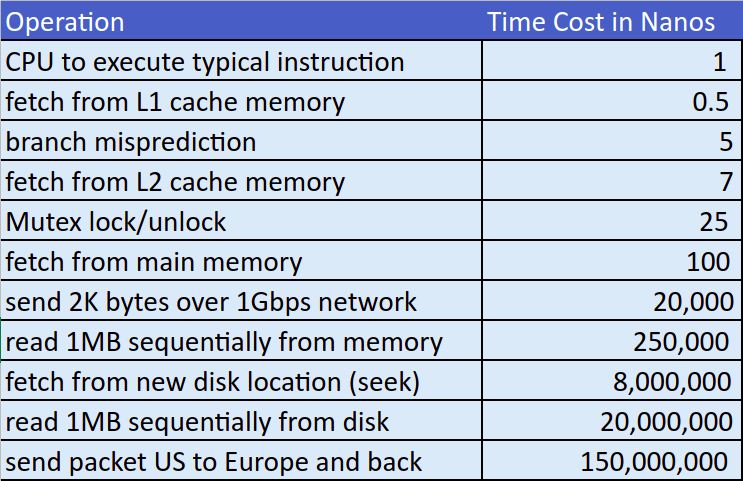

This table shows how long the CPU conceptually has to wait for data retrieval from various locations, which essentially is the “time cost” of various operations.

Clearly, in such a blocking situation, the CPU would theoretically remain idle for tens or hundreds of millions of CPU cycles waiting on data transmission to and from the network and local storage.

Luckily, in reality the OS would detect processes that are not utilizing the CPU, and take it away from them until some data arrives and starts filling up the respective IO buffers. Also keep in mind that while a TCP connection is an abstraction of a nice and smooth data stream, in reality, it is actually composed of discrete IP packets that may not arrive at uniform time intervals, or even in the right order!

Therefore, while a TCP connection “appears” to your Python OS process as continuous stream of bytes, in reality, it is far from continuous, especially for a larger HTTP payload, and the OS process will likely block multiple times until the entire payload has been fully received.

The process context switching associated with the repeated block-and-resume events during the lifetime of an HTTP request (or disk IO operation) in a single-threaded program is in itself a very costly and time-consuming matter which is inevitable if the OS process has nothing else to do but wait on a blocking data stream.

The multi-threading approach

A multithreading solution in Python is generally a good one as long as the number of threads at runtime is predictable, limited to a few dozen threads, not very CPU intensive (due to the Python GIL) and are not too short-lived.

Say we want pull and store prices of crypto coins in batches of 10 coins at a time (trying to be as nice as possible to the service provider serving this API). A single threaded program would look like this (excluding any error handling code for brevity)

import requests

# Generate url and filename for each batch

batches = [{'url': f"https://api.coinlore.net/api/tickers/?start={start}&limit=10",

'filename': f"batch{start}-{start + 10}.json"} for start in range(0, 100, 10)]

def process_batch(url, filename):

with open(filename, 'w') as f:

f.write(requests.get(url).text)

for batch in batches:

process_batch(batch['url'], batch['filename'])

A multithreaded version, using the Python thread executor would be almost just as easy, but significantly faster:

import requests

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

# Generate url and filename for each batch

batches = [{'url': f"https://api.coinlore.net/api/tickers/?start={start}&limit=10",

'filename': f"batch{start}-{start + 10}.json"} for start in range(0, 100, 10)]

def process_batch(url, filename):

with open(filename, 'w') as f:

f.write(requests.get(url).text)

executor = ThreadPoolExecutor(4) # only 4 threads beside the current, main thread

for batch in batches:

executor.submit(process_batch, batch['url'], batch['filename'])

executor.shutdown() # wait until all tasks are complete, then shutdown the thread pool

While multithreading context switching is remarkably less costly than process context switching, it still comes with some time and RAM overhead as explained in detail in this excellent article:

Thread VS Process Context Switching

For these two reasons (context switching and RAM overhead) multithreading may not optimal when it comes to dealing with thousands of IO-bound concurrent tasks.

The Async-IO approach

The main benefit of Async-IO programming is the ability to handle a huge number of concurrent tasks with minimal consumption of system resources, namely the CPU and RAM.

The Following code demonstrates executing 10,000 jobs in parallel, each simulating an operation that takes 2 to 4 seconds to complete.

import asyncio

from random import random

async def slow_job(num):

await asyncio.sleep(2 + 2*random()) # a 2 to 4 seconds operation

return num, num**2

async def main(count):

tasks = [asyncio.create_task(slow_job(x)) for x in range(count)]

results = {}

for coro in asyncio.as_completed(tasks):

num, num_square = await coro

results[num] = num_square

return result

from time import time

t1 = time()

result = asyncio.run(main(10_000))

t2 = time()

print(t2 - t1)

This code took 4.14 seconds in total to complete for 10K tasks in a single OS Thread. The breakdown of this interval is as follows:

4.00 seconds for the longest task across 10K tasks

0.14 seconds accounting for:

overhead of starting the loop

All instances of a process context switch as the OS scheduler timeshares the CPU across other processes

making 10K Python function calls including the creation of Python objects (tuples in this case)

Closing the event loop

Running 10K tasks simultaneously in a multithreaded program is of course out of the question, and getting anything near those results is practically impossible.

Async-IO Guidelines

Python’s approach to Async-IO has actually evolved over time, and has become very intuitive and syntactically sensible, especially in comparison to other programming languages.

The first guideline is understanding the nature of the tasks that should be run in an asyncio event loop, and ones that shouldn’t. One mental habit that I have developed is to try to categorize every statement and function call in the program flow into one of the following categories:

IO Bound (read and write to and from local storage, the network, or asyncio polling)

RAM Bound (Indexing and Iterating over data structures)

CPU Bound (tight loops of numerical or logical operations, cryptography, hashing, and similar)

Ideally, all tasks running on an event loop are purely IO bound, using the proper libraries and asyncio APIs, and avoiding CPU heavy operations. CPU bound tasks are better run in separate OS processes entirely, to take advantage of multiple CPU cores whenever possible.

Ideally, code blocks containing a mix of IO and CPU heavy operations are broken into separate units such that each can be run in the more suitable context.

Which brings us to the next idea: in larger, more complex applications, it can sometimes be tricky to figure out if a function could, must, or mustn’t be run on the event loop.

For instance this function can only be run in an asyncio context - it is defined with the async keyword, and it has one or more await statements in its code block.

async def function_1():

await function_2()

This one can be run on the event loop, but shouldn’t. It is not a good idea, because it is very CPU intensive function - better run it in a separate thread or a separate Process.

def squares_and_roots():

import math

return [(x, x**2, math.sqrt(x)) for x in range(1000_000)]

This function MUST NOT be run on the event loop. It will block the entire thread and other async tasks from running for a very long CPU period (tens of millions of CPU cycles). This is probably the most common bug / mistake in larger asyncio programs, and usually happen without a warning.

def read_file(filename):

with open(filename) as f:

return list(f.readlines())

This function is valid - but it shouldn’t have been declared with the async keyword, since it doesn’t contain await or call asyncio functions that need to be called from within the loop.

async def add(x, y):

return x + y

This last example is the trickiest. func_1 and func_2 aren’t declared with the async keyword, nor do they contain any await statement, but surprisingly, they must be, and can only be invoked from an asyncio thread, and would actually raise exceptions if run outside the loop.

import asyncio

async def sleep():

await asyncio.sleep(1)

def func_1():

loop = asyncio.get_running_loop()

return loop

def func_2():

asyncio.create_task(sleep())